One of the oft-cited reasons for investing in commodities is that they have historical returns comparable to stocks while having a low correlation to the stock market. The problem is that this statement is patently false.

Yes, commodities used to have low correlations to stocks. But that was before the era of “financialization” and securitization.

In their 2011 paper “Index Investment and Financialization of Commodities,” Princeton University Professor Wei Xiong and Renmin University of China Professor Ke Tang prove empirically what many of us in the profession have long suspected: Commodities and commodity stocks are becoming more highly correlated to each other and to other asset classes.

Furthermore, while the prices of individual commodities have always been volatile, commodity prices as a whole have also become far more volatile in recent years.

The question begs to be asked: Why?

Tang and Xiong place the blame on the slew of ETF and mutual fund products that offer stock investors passive, indexed access to commodities. Whereas the equity and commodities markets used to be populated by very different types of investors and traders, there is now almost total overlap. It’s hard to find a traded commodity that doesn’t have an ETF or ETN that tracks it; the commodities market has become the stock market, and volatility in the one spills over into the other. The end result is that virtually all commodities track the price of oil now, and oil in turn tracks the stock market.

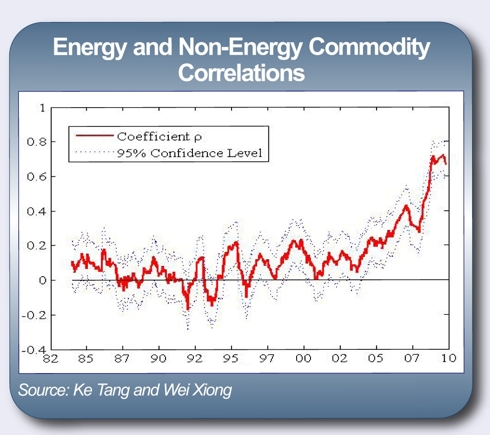

Take a look at these charts. Prior the mid-2000s, energy and non-energy commodities had very low correlations (the line hovers near zero). The economic factors that drove oil prices were very different from those driving the price of, say, cattle. But after 2004, correlations started to rise.

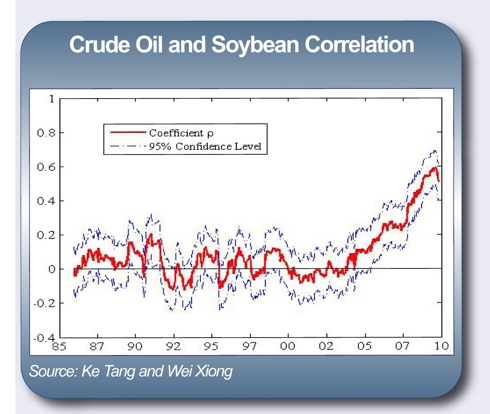

We can see this in two commodities as seemingly unrelated as crude oil and soybeans, via the chart in the middle. Correlations hovered around zero for decades before suddenly spiking upwards.

It’s easy enough to understand why. As commodity investments became popular in the mid-2000s, investors started buying and selling commodities as a homogenous block in index ETFs and mutual funds rather than buying and selling individual futures contracts. Fundamental analysis of the supply and demand characteristics of individual commodities no longer matters when they are collectively bought and sold in a lump.

It has become common to blame the increased rise in correlations on the emergence of China and other developing countries. China is consuming more of everything, therefore the price of everything is rising together.

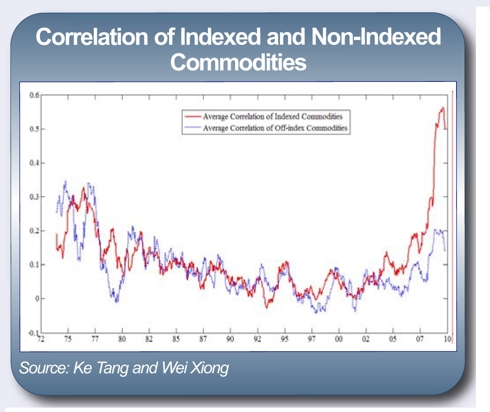

The problem, again, is that this simply isn’t true. The final chart at the bottom compares the correlations between indexed and non-indexed commodities. Indexed commodities—those that are included in popular indexes that the commodity ETFs are based on—have much higher correlation than those commodities left off the index. Furthermore, the professors point out that the Chinese commodities markets—which are off-limits to foreigners and index funds—have been far less correlated than the American markets.

This is what George Soros describes in his Theory of Reflexivity. Soros is highly critical of the Ivory Tower view that markets are efficient and that prices reflect fundamentals, insisting instead that fundamentals also reflect prices in a circular feedback loop. In other words, in trying to buy assets with low correlations to each other, investors have unintentionally caused the correlations to rise.

When academics first suggested commodities as a portfolio diversifier, they failed to understand how a massive increase in investor interest in the sector would affect the relationships between stocks and commodities and between the various commodities themselves. Call it the “Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle of Finance,” if you will.

For investors today, this means that one of the primary reasons for including commodities in a diversified investment portfolio— the low correlation to stocks—is now largely moot. Talented speculators can still make a bundle trading commodities, of course. But longer-term investors would be better served allocating their funds elsewhere.

Tang and Xiong’s complete research paper can be viewed here.

Charles Lewis Sizemore, CFA

This article first appeared in The Sizemore Investment Letter, a monthly subscriber-only newsletter.

If you’re not reading The Sizemore Investment Letter, then you are missing out on rock-solid investment recommendations designed to profit from the major macro trends shaping the world today.

SUBSCRIBE TODAY and get access to information that is simply not available anywhere else.

I agree with your premise that correlations are way up. Furthermore I believe that simply investing in commodities by buying a basket of them is silly. However, by placing funds with a tallented CTA, CPO, or even a tallented broker is a good way to diversifiy in commodities. That is because these entities speculate in them. Futures are not a buy and hold asset. I really liked the article.

Thanks,

Paul Kogut

Futures Connect